By Peter @Newton Bell, 29 December 2016

Following on our discussion of the Proust Questionnaire, Brian Leni and I turned our attention to the markets. We talked about Brian’s series of articles on the uranium and lithium markets, and I learned that production from brines can vary greatly depending on weather. I put some questions to Brian about the implications of the cost declines of solar and we even talked briefly about the potential of thorium reactors! Find all that and more below.

>>

P: It’s the end of the year here – 2016 – and it’s been a wild year for our segment of the markets. We just had another rate hike here recently from the Federal Reserve, so I wonder if January 2017 will resemble the one just past.

B: Tough to say. Personally, I don’t know what to think.

P: I remember sitting there in January, watching things happening and being scared out of my wits!

B: I try not to focus on the short-term, but I think some things still make a lot of sense. For example, the gold thesis has never been better. It’s still “not if, but when.” The short-term fluctuations are probably going to prove to be good buying opportunities as people realize you can’t just keep going into debt to solve our problems.

P: Developments around the world continue to be staggering. Whether its India overnight changes to what counts as legal tender, or all the stuff happening in the Middle East. There was some nasty news recently about Israel, an outcome that they didn’t want at the UN regarding Jerusalem. Tensions in the Far East, too. And the USA approved a $600+ billion dollar military spending package a couple of days before Christmas. Same as it ever was, I guess.

P: You had a big piece out about lithium there, about the supply and demand fundamentals. Any comment on what it was like to do all that research there? (Lithium)

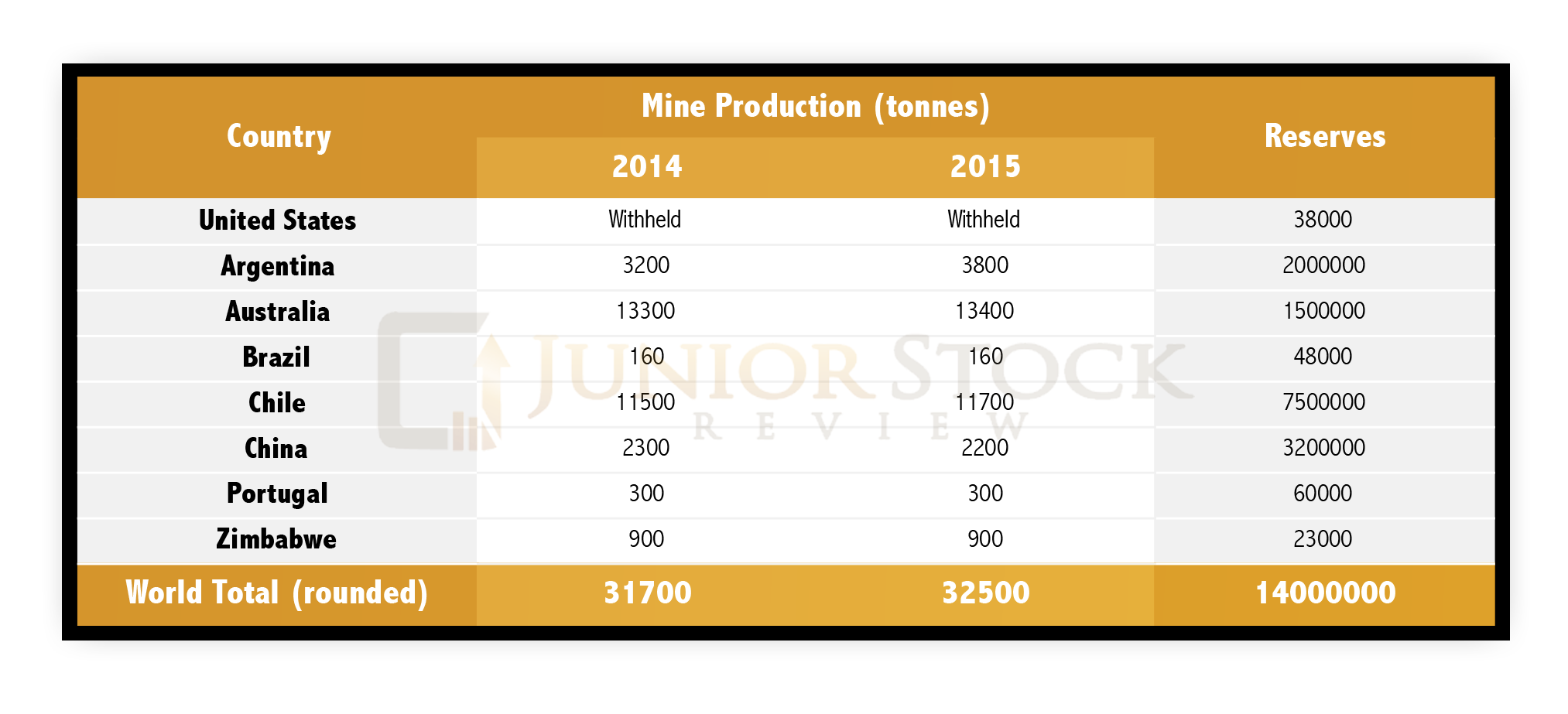

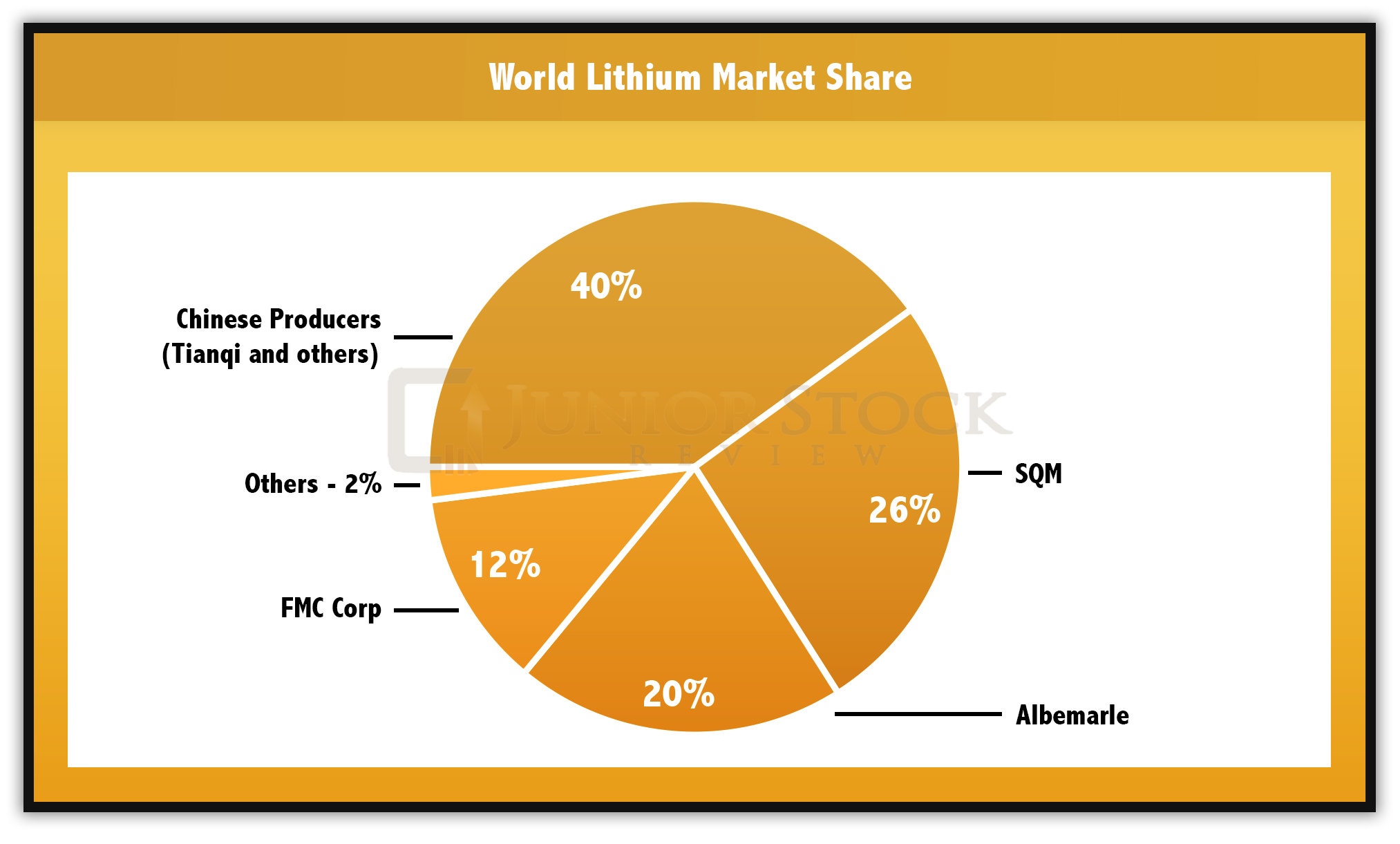

B: The lithium market is very interesting. For a metal that, I believe, is going to be in high demand over the next couple of years, it’s hard to find and put together the information for supply and demand dynamics. The market is still very small. There are four main players. You’re talking about concentrations of production coming predominantly out of the lithium triangle in South America – that’s Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, and the main hard rock source from Australia. The rest of the world is in a race to catch up.

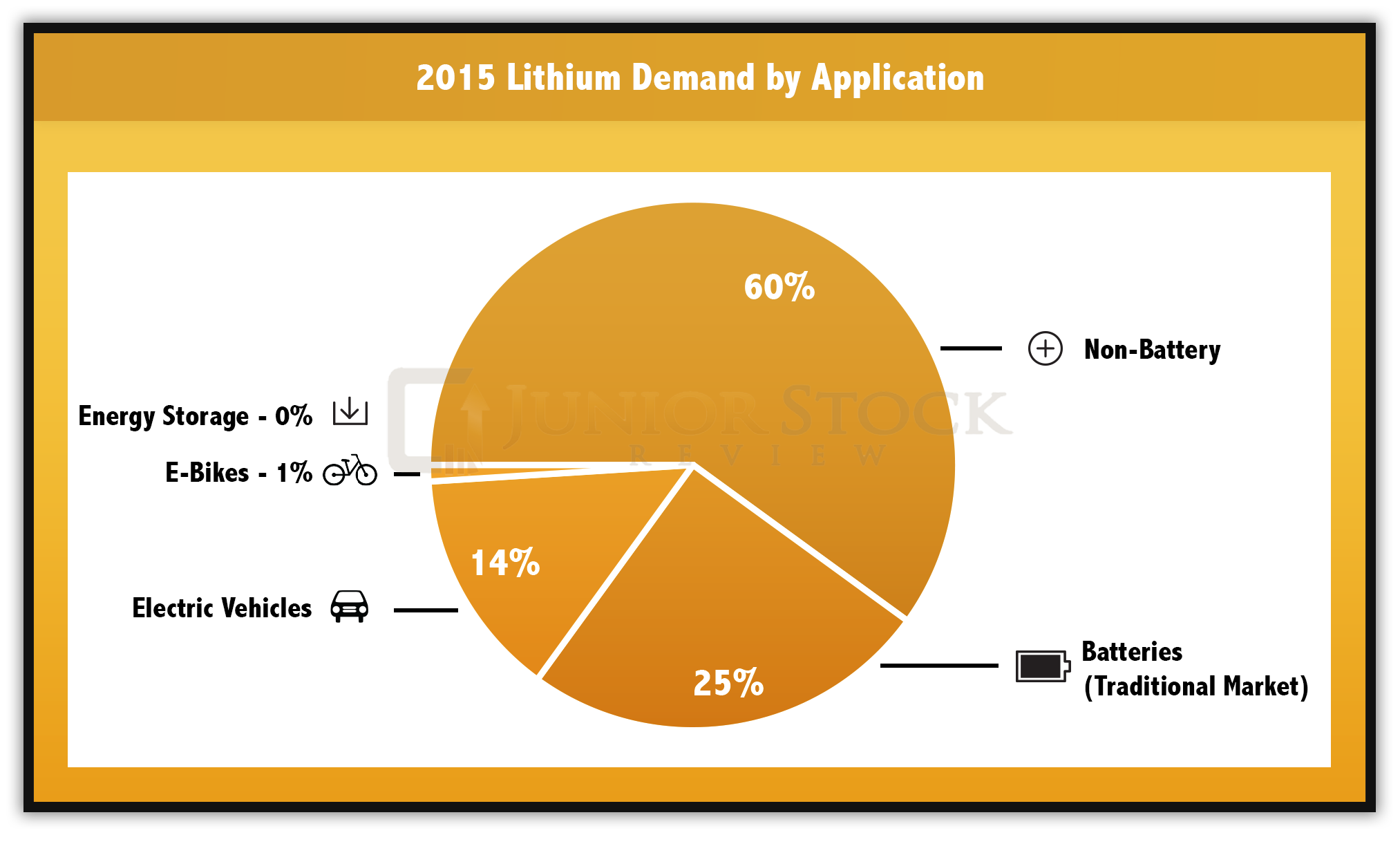

B: When the gigga-factory and the electrical car movement really starts to hit its stride, it will be a scramble to meet that demand. It’ll be interesting to see how this plays out.

P: It’s tough because I’ve heard Rick Rule say there are enough known reserves to satisfy demand for a long time.

B: Chris Martenson, of PeakProsperity.com, has some relevant theories that can be applied to that. He has a line of analysis where he explains the concept of peak oil. Most people think of peak oil as “we’re going to run out of oil,” but he points out that it’s not necessarily the case. There are massive oil reserves and even more that we have yet to find. What may end up being more important is the rate at which you can extract the oil versus the rate it’s consumed; inflow versus outflow.

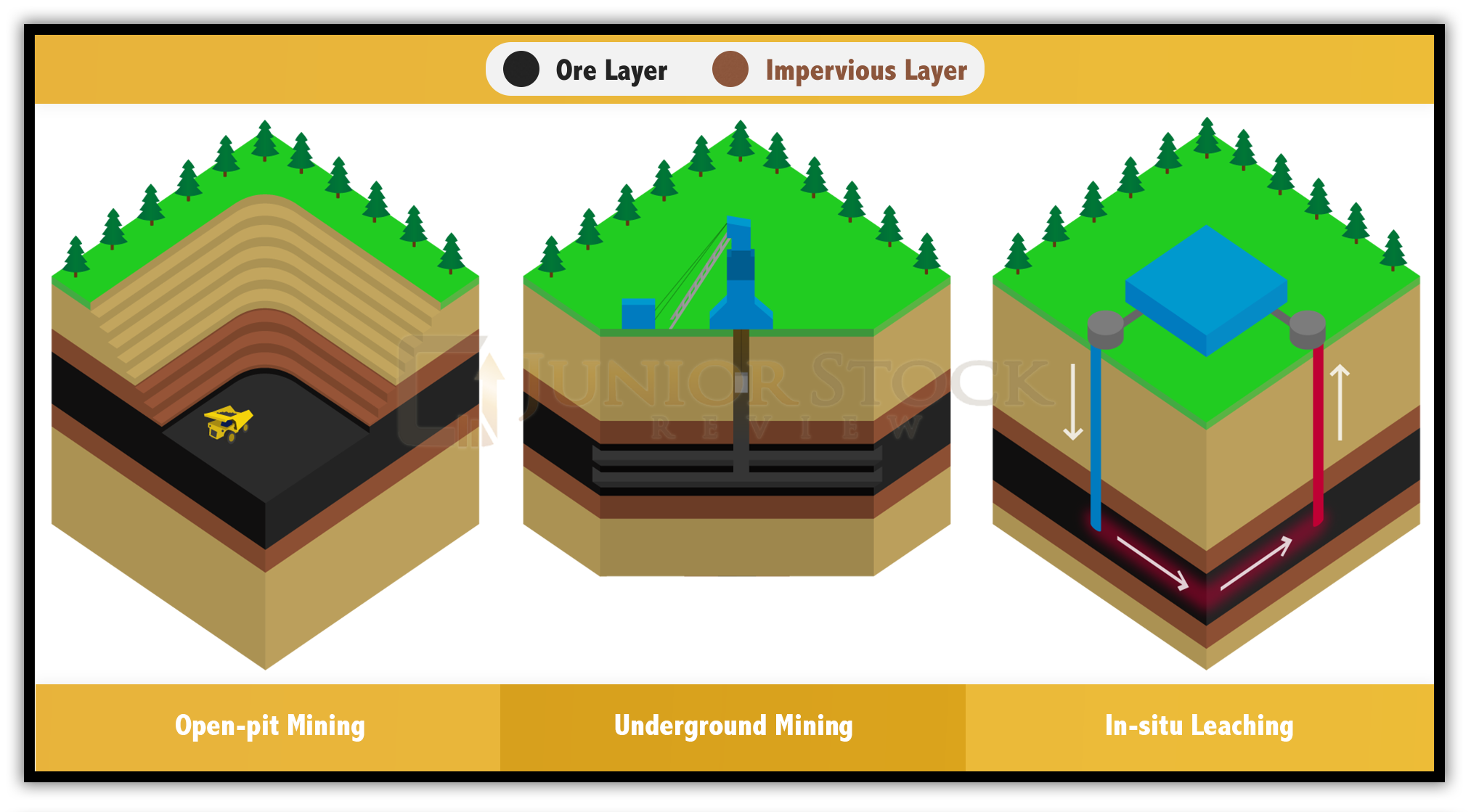

B: A similar argument could be made for lithium. While there are significant lithium reserves in the world, the rate at which they can be harvested is going to be, in my mind, the sticking point. Simply put, there are typically technical issues with bringing these deposits to production, and especially with brines. The brine settling ponds are impacted by the weather, with evaporation being a key aspect of the refinement process. Therefore, any changes in weather patterns in the world could wreak havoc on this process, hurting production figures.

B: I don’t disagree with Rick. There are a lot of known deposits of lithium out there, but I think it’s more complicated than just referring to the number of reserves that exist in the world.

P: Well, that’s something I haven’t heard before — the variability in the production from the brines. If we’re talking about a market with a few large sources of supply and these sources have great potential variability caused by weather, then that is a very interesting set up for tightness in the market.

B: Definitely. The lithium triangle in South America is the premier source of cheap lithium. Politically, Argentina has changed dramatically with their new president, and South America as a whole is looking pretty good from a political risk perspective, but who knows how the Trump effect could reverberate down there. If he decides he wants to add tariffs to certain commodities, he could add a source of instability to the lithium market.

B: Suppose something did happen to brine production in the lithium triangle. You could, conceivably, see half of the global production of lithium come offline. That would be a serious development that could have major impacts under the current demand profile, let alone in a growth scenario. I don’t know what is going to happen, but it is very interesting to see how all these different things could significantly affect this relatively small market.

P: Right. The growing demand profile for lithium always seems to be the thing that gets people excited.

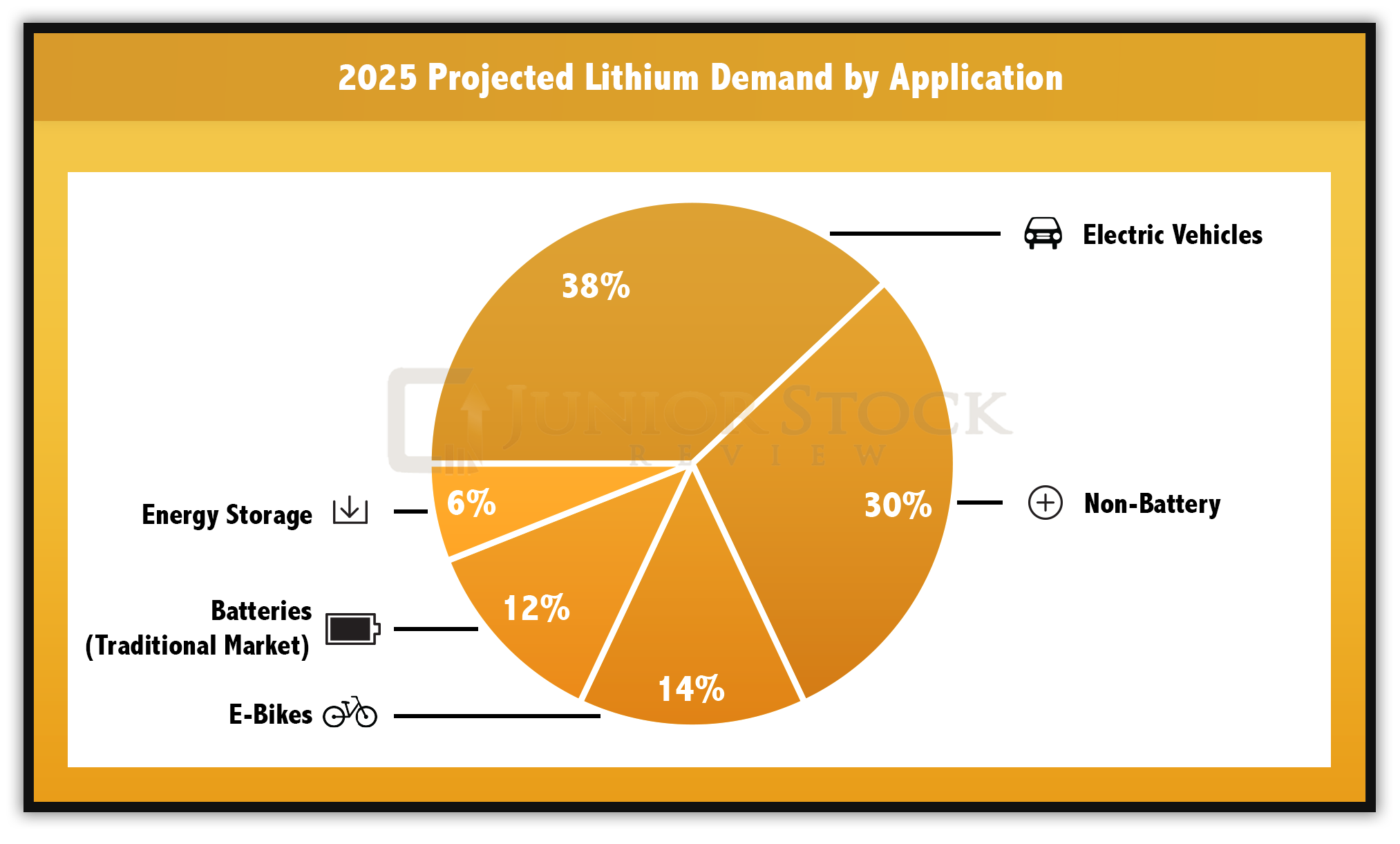

B: Yes. The Paris accord was passed last year — lots of press around that. And the International Energy Agency has something called the 450 Scenario, which calls for reductions of carbon emissions to achieve global concentrations of greenhouse gasses of 450 parts per million. They plan to do that in segments – by 2040. For example, if the United States is to comply with the reduction of carbon emissions related to vehicles, they will have to reduce their emissions by 3%.

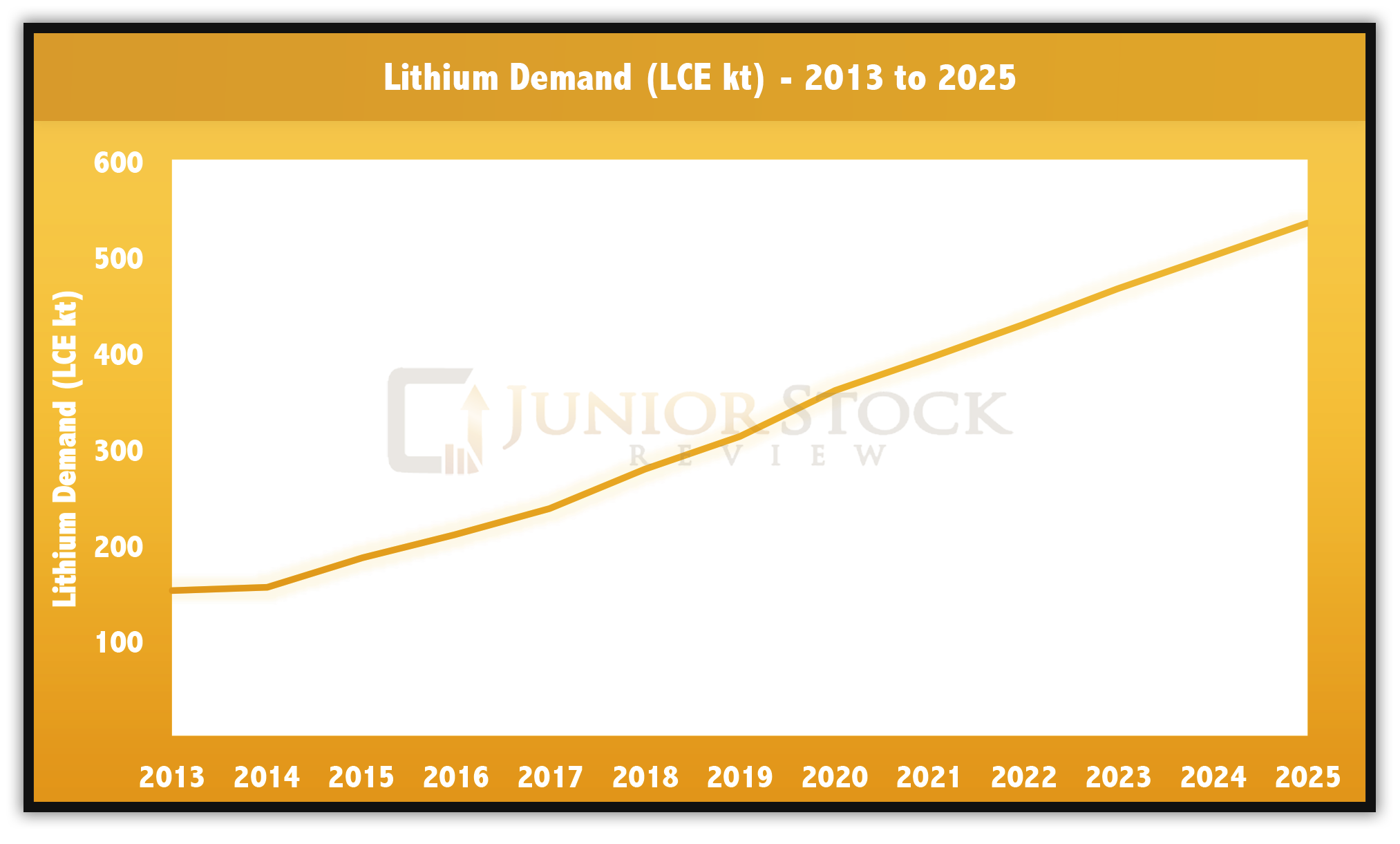

B: Deutsche Bank came out with their forecast for lithium demand, which I cited in my report. It was a linear distribution going out to 2025. From my experience, not much in real life follows a linear path, it is typical exponential growth that dictates most behaviour. If demand increases faster than expected, it becomes about how fast you can get the lithium out of the ground to meet demand. It might not be a long-term demand squeeze, but the setup is there for at least a year of huge volatility. The markets may be able to get it under control by bringing on other sources of supply, in line with what Rick has said, but you could have short-term fluctuations with major price swings, in my opinion.

P: Well, I am curious to learn more about the potential for declines in lithium brine production caused by weather. The bits and pieces that I’ve heard about the engineering aspects of brine production are very interesting. Any other commodities that you’d like to discuss here?

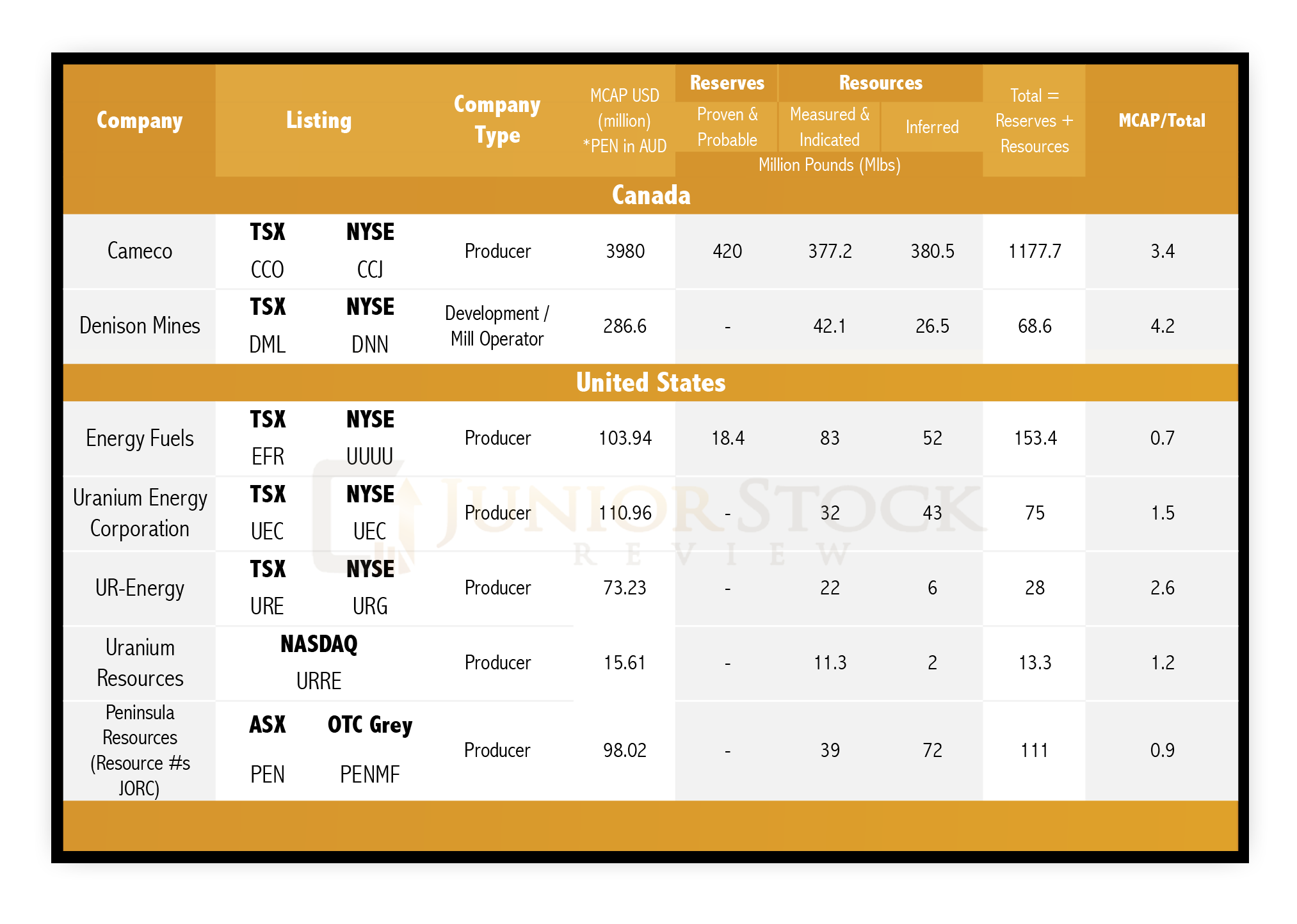

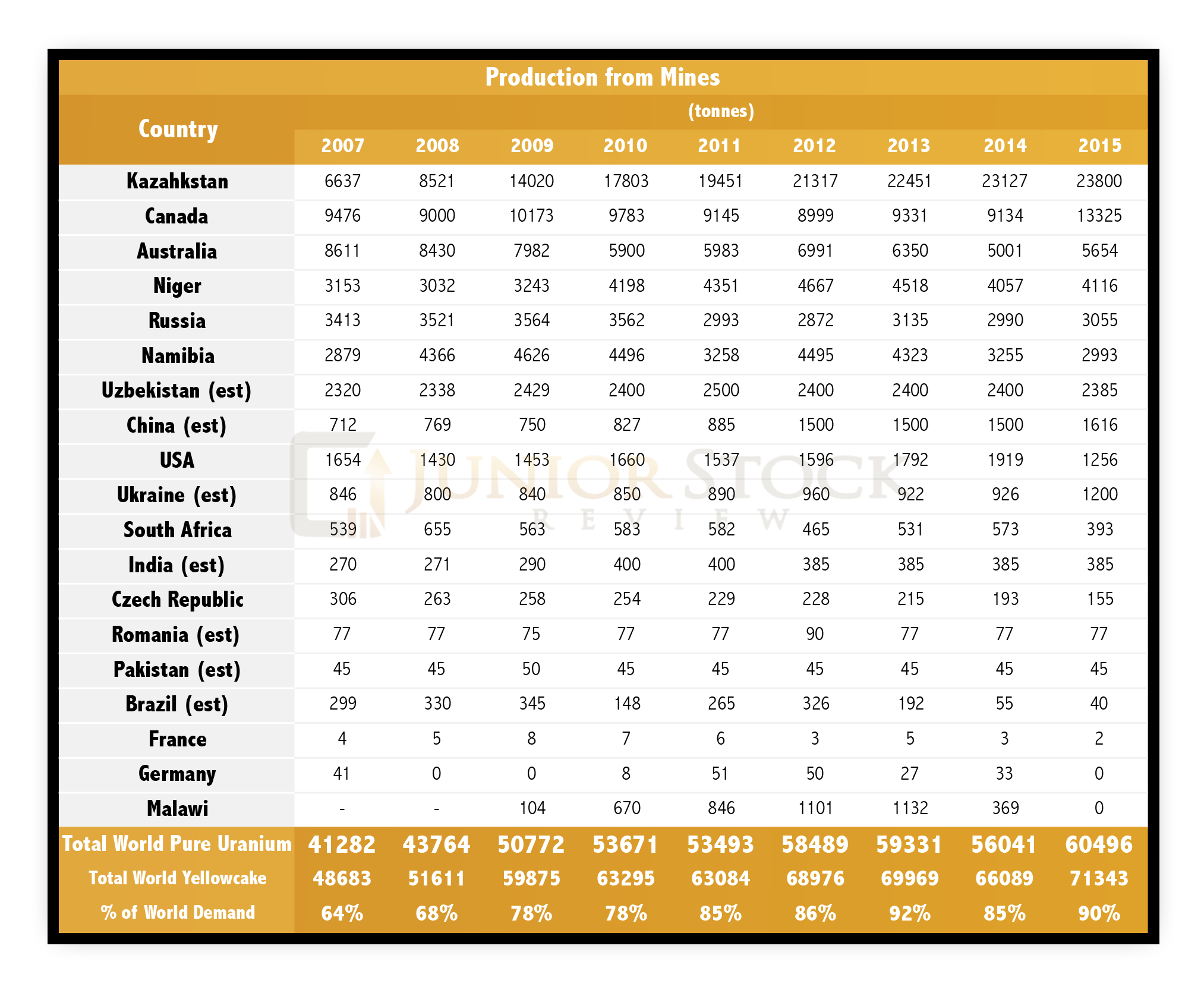

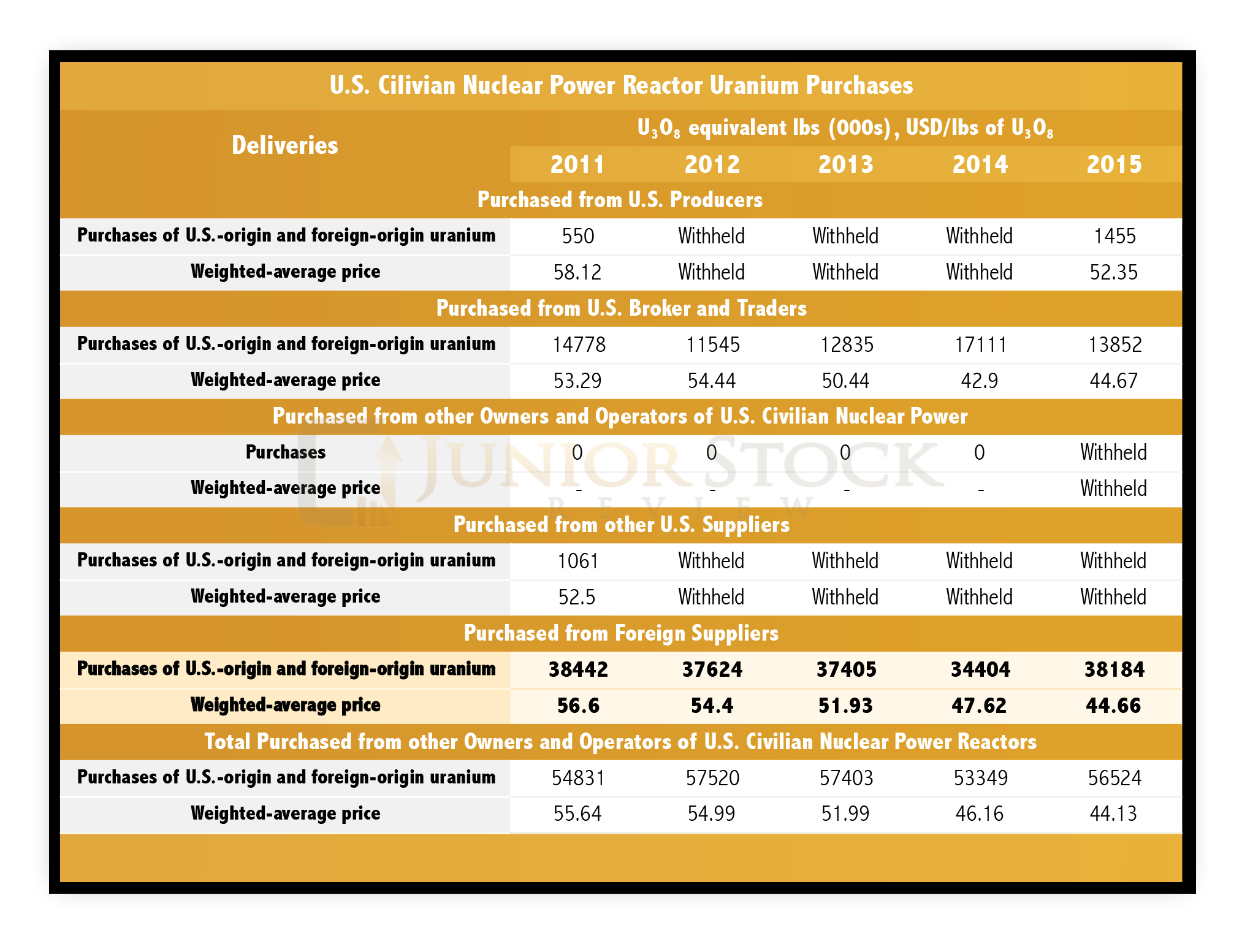

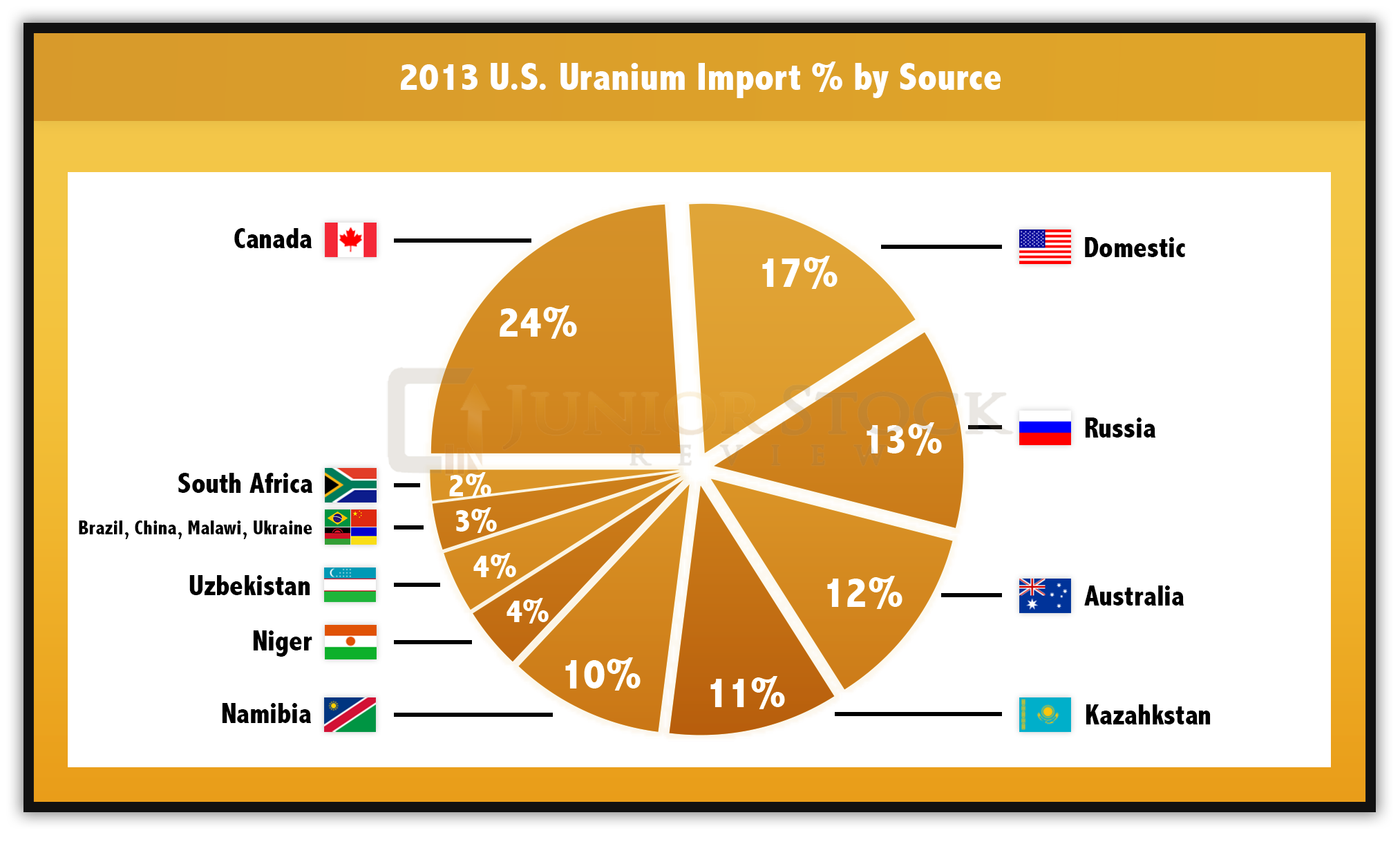

B: Despite my interest in lithium, I tend to concentrate on things that are out of favour. For the last two and a half months, I’ve written a four-part series on uranium and why I think the future is bright (Uranium Scenarios – Part 3B of 4). The more people who doubt it, the more I like it. I think it was Marin Katusa who came out a couple of weeks ago and called a bottom in uranium prices. Time will tell if he’s right, but it is better to be early than late for this one, I think!

P: Any comments on solar and wind, broadly, as competitors for nuclear energy?

B: Yes. I see a couple of things to discuss there. Typically, when people are talking about alternative energies like solar and wind, they’re focusing on the environmental impact. If you compare it to nuclear power, neither have any direct carbon emissions. If you look into the construction and fabrication of solar cells and wind turbines –it all requires mining.

B: Some of the European data I’ve seen suggests that nuclear power actually has a lower carbon footprint than renewables. You can then look at the physical footprint of the renewables. The footprint for wind turbines can be quite large and they often take up a lot of farmland. I live in a part of Ontario where there is a lot of controversy over windmills, because people don’t want to live next to them for a number of reasons.

B: And, with solar farms, the efficiencies on the photovoltaic cells are pretty poor right now. They need to create huge solar farms to produce enough electricity to register on the grid. In Canada, we live north of the 49th parallel, and the amount of sun is pretty low in comparison to some of the southern States or countries across the equator. I don’t think solar is the answer for baseload power either, at least in its current technological state.

B: If people can get over the fact that there’s radioactive waste then uranium is the obvious answer. In the long term, the uranium business will change as the industry is coming up with new types of nuclear reactors. These new reactors are going to use what we now consider to be nuclear waste; material with well under the 3.5% U235 fissile material that’s commonly used as fuel.

P: I’ve heard troubling comments about the cost declines in solar — negative electricity prices on spot markets during mid-day in some of the deregulated markets, like California and Germany.

B: I don’t know much about that. In Ontario, at least, there was a feed in tariff programme where the provincial government gave 20-year contracts to power producers, large and small, for fixed prices somewhere between 75c to $1 per kWh. That is significantly above the peak rate that we pay for electricity in Ontario, which is around 10c. A lot of the market is still subsidized and somebody is paying for it in some shape or form. It would be interesting to see what the actual cost is to produce renewable energy in Ontario, all in.

P: Well, the issue of non-market actors coming in and doing things to help seems to be a big issue throughout history. Getting in there and distorting the price signals.

B: Absolutely.

P: Commodity markets are prone to exaggeration at the best of times, I think, but add in some government assistance and that can just make things all the more complicated. Distorting the signals is a big deal — seems to me that they can cover up problems in the short term, allow them to persist, and develop into something bigger.

B That seems to be why government intervention generally doesn’t work — you can’t create these imbalances. An example from the natural world, we tried to fix the problem with the Purple Loosestrife plant in Ontario by bringing in an African beetle to eat it. Which, on the surface was great; they solved that problem. But, what happens with this new influx of beetles? The solutions can cause more problems and things can get out of hand quickly. Somethings are meant to die — it’s sad, but it’s part of life. You have to let it happen.

P: And investing around that — I guess that’s why we get painted with the brush of being evil speculators sometimes.

B: That’s right!

P: To change gears a bit, does technological change that figure in prominently to your thinking and investing? I see it there in the uranium industry, but I suspect that it may be hard to invest in that yet.

B: They’ve got these fast neutron reactors that are being tested in China and in Russia, and there’s also thorium reactors. Thorium reactors are interesting because thorium is much more abundant in the world and the waste isn’t as much of a concern. It’s something the Chinese are really pursuing, but their dates for these things are far away — maybe 2040 or 2050.

B: My thoughts are that most of this technological change is exponential. You could plot a linear path as much as you like, but when things follow an exponential path, it could be upon us before you know it! As such, I think the next boom in uranium is going to be great and there may be another cycle to be had before we get to the next generation of technologies — I think uranium is one of those things that you take it one cycle at a time. Don’t try to get too ahead of yourself about what might happen in 20 years because so much can change by then.

P: I’ve heard a distinction made about growth markets versus dependency markets, which has been helpful for me. Coal is, apparently, an example of a dependency market because it is still essential commodity, but there’s not a lot of new coal demand coming on stream and that doesn’t really incentivize exploration. Its not really a sexy business to be in. From that perspective, the rally in coal prices this year will undo itself by bringing forward some of the known production sources — it’s not the start of a long-term bull run in coal driven by new demand sources. I wonder if uranium is moving in a similar direction. I recognize there is a lot of new demand coming onIine from nuclear plants around the world, but wonder how technological change may affect that in the future.

P: Anyway, I’ve always enjoyed hearing about the thorium stuff there and always loved to hear how rare earths and thorium are often found together. I feel like that is really futuristic stuff there — a host of next-generation metals from one source.

B: This is off topic, but some of Nikolas Tesla’s free energy theories are just incredible. Some people say that the stuff he was working on actually exists, but has been supressed because there’s no profit to be made. Who knows, but if you want to talk about revolutionary — free energy could change every aspect of our lives and society. We fight most of our wars about energy, so it’s interesting to think what could happen if energy were free.

P: That’s always been something I’ve liked about the world of junior stocks — you need a bit of optimism and hope that you could change the world for the better. It can be as simple as creating jobs in a place, or as big as new types of nuclear power. Maybe we’re both new to it, but that ambition always appealed to me.

P: So, can we expect to see you actively writing in 2017?

B: I’m looking forward to publishing some stuff in the next couple of weeks, here. And I’ll be at the Vancouver Resource Conference and PDAC, as well.

P: Well, please post some updates to CEO.CA so we can follow along. Thanks for the chat, Brian, I look forward to talking again with you.

B: Thanks, Peter. My pleasure. All the best for 2017.